Intention (n) – a purpose, goal, plan, ambition, and/or hope

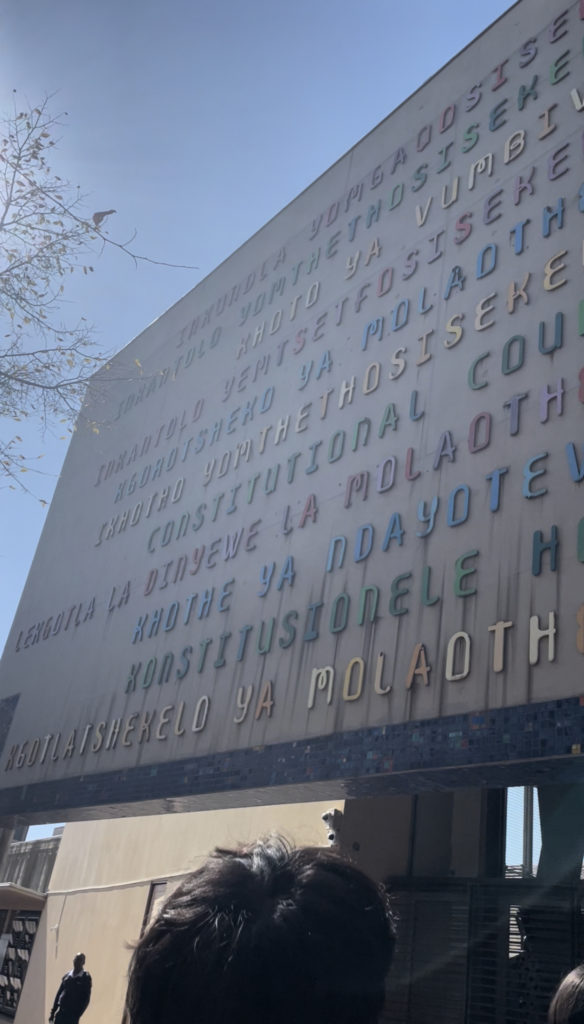

If there is one word that I can use to describe what I found most inspiring about today, it is the one above: the thoughtfulness, the intent of everything that went into creating the Constitutional Court. When Paul and Jonathan mentioned that we were going to tour this building, my mind automatically envisioned the looming, columned buildings of the Supreme Court back home. Instead, what greeted me was a rainbow colored sign and an extremely tall wooden door inscribed with large numbers, cursive words, and hand gestures. I was confused. Had the shuttle brought us to the right place? I didn’t see an obnoxiously large number of steps leading to a grand entrance, the pristine, uninviting white marble was missing, and where exactly was the division between the court and the rest of us? But no, that couldn’t have been possible; Del would have never let our instructors take us to the wrong place, so I followed everyone up to the hill where Lwando Xaso stood and eagerly waited for her to take away my confusion.

She succeeded marvelously. I remembered some of the historical details from the Apartheid Museum: the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the start of apartheid in 1948, the turbulent negotiation years in the 90s. What I didn’t know, however, was that the place that housed the constitutional court of South Africa, a place that represented truth and justice, the place that my black heels were clicking and clacking on, had originally been created as a prison of oppression. Here, at one of the highest points in the city, I could see the history of the holding block, the experiences of the black men and women that were unjustly held in this red-bricked building during apartheid, forever preserved in the three pillars left standing.

This same red brick appeared again during our tour of number 4: the black male prison. If they say that beauty is pain, then number 4 is the most beautiful place I have ever seen. As we went through the dismal conditions of the prisons, the Tausa, the solitary confinement, I remember Lwando asking: “What is a prison for?” I got to thinking. For the apartheid state, it was a weapon of control, a sword of humiliation, a regime meant to oppress black people. For the United States, though…

It is a weapon of control, a sword of humiliation, a regime meant to oppress black people.

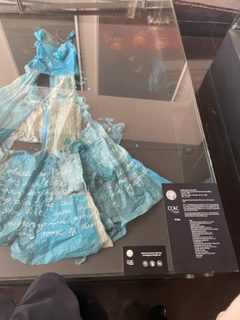

As we walked out of history and back towards the tall, wooden doors of the Constitutional Court, I remembered my initial confusions and finally found answers to them. The space was built to be inviting, built to be the building of the people, meant to create a unity that had been long lost during apartheid. Formerly a prison, the Court symbolized transformation and the power of art in healing and justice. I think back and I can picture the Court’s slanting pillars and hanging leaves that symbolized a tree, the court’s emblem of justice. I see the ladder representing South Africa’s history and think of the bright red letters behind it reminding us that the struggle continues. I remember the dress made of blue plastic bags and the heartbreaking story of The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent. I feel the power and conviction of Mandela’s words and proceed to ask myself what ideals I’m willing to die for.

What sticks with me the most, however, is the ability of South Africa to accept its history, its intent in recognizing the oppression, exploitation, and injustices South African history contains. As Lwando’s voice passionately read out the preamble to the South African Constitution near the end of our tour, I was left with one final thought: how beautiful would it be if our constitution one day began with…

“We the people of the United States recognize the injustices of our past…”