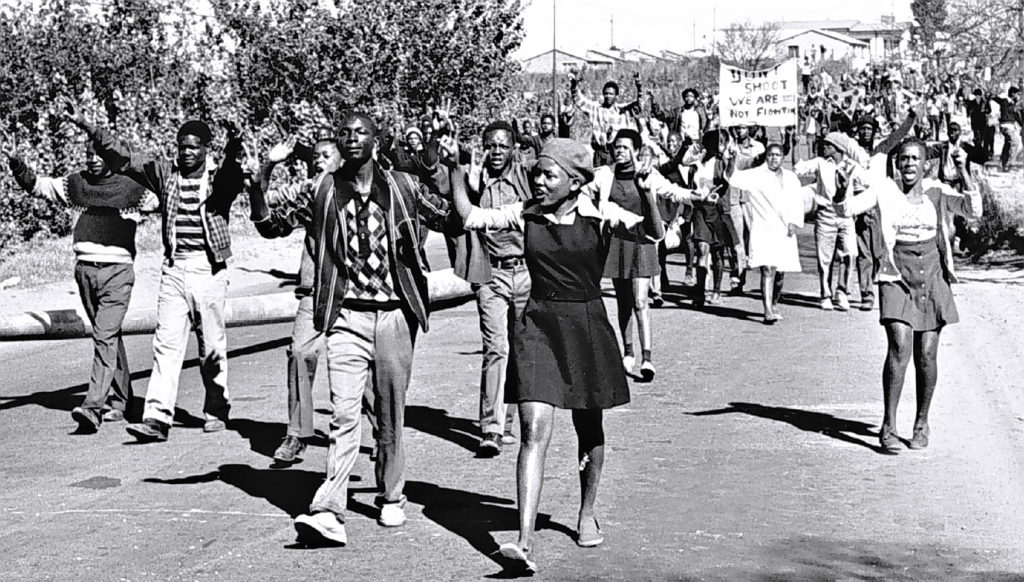

I think it’s natural for us to go into unknown environments and begin comparing what we see to our previous experiences. I keep thinking back to Colombian landscapes or American history as we get to know Johannesburg. During today’s visit to Soweto, a city that looks nothing like the American urban spaces that I’m familiar with, my mind kept going back to the 1963 Children’s Crusade in Alabama. In 1963 Birmingham, children stepped up to fill the streets and the jails to protest segregation. Thirteen years later in Soweto, children risked their lives and liberty to march against Apartheid-era educational policies.

Soweto on the top, Birmingham on the bottom

At first, my pain in response to the role little children played in violent uprisings against unjust conditions led me to the simplistic conclusion that the only difference between these two events is the subsequent national memory and how this shapes modern perceptions of the youth in each of these two countries. This observation was again influenced by emotion since my anger at the current disregard towards school shootings by many in the US and my irritation that I only learned about the Children’s Crusade last semester drew my attention to the lack of concern Americans seem to have for the role of kids in the Civil Rights Movement, in contrast to South Africans.

However, as I was preparing to write a pessimistic blog about the repetition of historical patterns and the power of memory as demonstrated by the different perceptions of youth movements in the US and South Africa, I realized how much I was simplifying the comparison between these two events. Overlooking the different historical contexts, the differences between apartheid and segregation, the variation in police and political responses, and much more, I fell into the same trap that I’ve criticized others for when it comes to the famous parallel between the Civil Rights Movement and X-Men comics. This led me to question why comparing the novel with our previous experiences is such an immediate response and what value we truly draw from this process.

Beyond psychological reasoning likely related to prototypes or something like that which I do not have the knowledge to discuss, I think there is an emotional component to these types of comparisons, and they do not simply stem from a desire to understand the unfamiliar. At least based on my experiences today, this instinct might be a result of the feelings evoked by a person’s first exposure to a new topic. The Hector Pieterson Museum made me feel anger that reminded me of what I felt as I watched The Children’s March, a documentary about the events in 1963 Birmingham. This emotion is also what made the comparison seem clear and unquestionable before I thought it through more clearly. Disturbingly, I wonder if we make these comparisons in search of some weird degree of comfort; perhaps it’s an effort to normalize what is shocking. Maybe we search for similar events that are more familiar in the hopes that what we are witnessing is not an isolated occurrence because something horrible only happening once draws attention to its unparalleled and extraordinary horror. For me, it had the opposite effect since I found the pattern more disturbing.

I have no idea why this comparison was at the forefront of my mind the whole day, and I’m just reflecting on my emotions to comprehend something that a psychologist could probably explain to me in a few minutes, but this is also helping me understand what benefits I got from this simplistic connection. It didn’t bring me comfort, nor did it really improve my understanding, but it did add fuel to the fire of the emotional reaction that helped me process the exhibits and shine a light on patterns and themes that can generally help in comparative political thought.