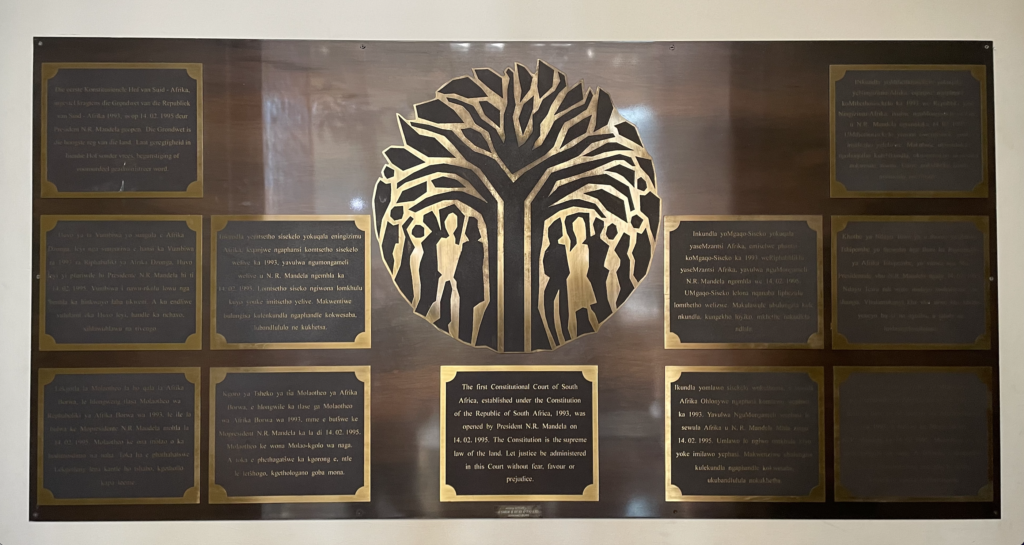

In the making of the Constitutional Court of South Africa before its establishment in 1994, human rights lawyer Lwando Xaso—who personally toured us around the area—revealed that the structure was modeled with a distinct, daring question in mind, “How do we put a smiling face on the justice system?”

The entire building was constructed with the same red bricks used in the prison complexes of Old Fort, Constitution Hill, where tens of thousands of Black prisoners were subjected to inhumane living and labor conditions while their White counterparts received preferential treatment from their wardens and even a cake on Christmas Day. Rising on the same land—with three untouched pillars—as the same place that represented a dark history of racism, repression, and resistance, the Constitutional Court was meant to be a transformation of hope where Black South Africans could reclaim their past and use it as a landmark of freedom, equality, and dignity within their new constitutional democracy.

However, while I was deeply moved and in complete awe of how the space was carefully deconstructed and then metamorphosed with such intentionality, I couldn’t help wondering how much had actually changed outside the visual symbolism presented within the chamber. As I continued to think about the question, “How do we put a smiling face on the justice system?”, I began to reflect on how a smile has a myriad of meanings depending on context, emotion, and appearance.

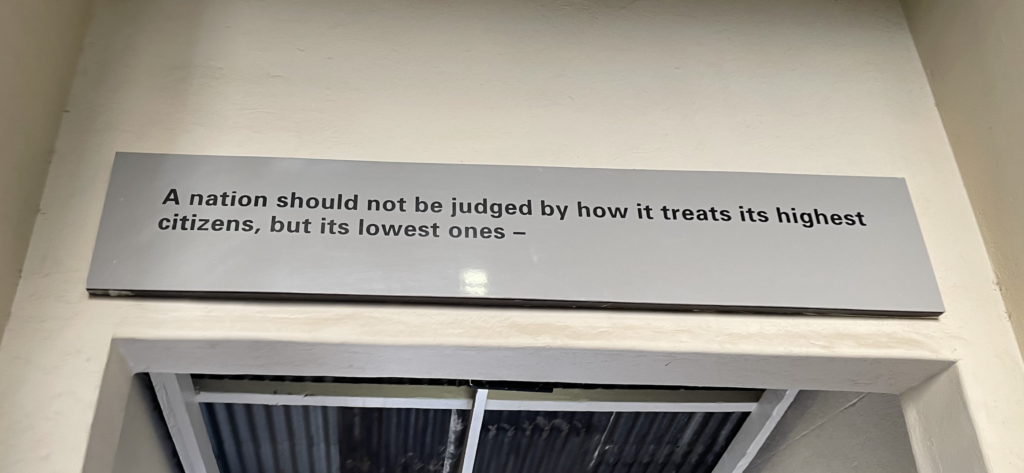

Cautiously, I let myself wonder, What if the justice system smiles sadly—helpless in its attempts to fully right the wrongs of the apartheid because it recognizes the disconnect between the written law and the reality its people live today? Conversely, I thought, What if it smiles in hiding—putting on a facade that makes it appear as welcoming, inclusive, and accessible as it was intended to be; yet these markings of transformation are also what blind the people into thinking that things have truly changed?

Although the building is lauded for its deviance from other international constitutional courts that flaunt their grandeur through glistening white halls and intimidating marble pillars, the lack of “walls” within—meant to connote a sense of transparency—still endures in stark contrast to the invisible “borders” that mark the country and its people so. There are lines drawn everywhere that separate the wealthy from the impoverished, the former oppressors from the former oppressed. They are the borders that existed during the Apartheid decades ago, and yet no law in the Constitution has been able to break them down.

I remember on our third day here, Manu and I went to River Walk nearby because we wanted to explore and stroll around the mini waterfalls we saw on Google. To our great surprise, we found ourselves in the middle of two very different places within the same area. To our left, a great expanse of beautiful flowering trees, nature nearly painted to perfection with fresh water flowing as clear as glass, and two lines of mansion-like houses on either side (this was their backyard, apparently), creating a bubble of little paradise where you could continue walking on for hours, basking in the light the sun, and still be within the bounds of safety. To our right, we saw immediate piles of trash, barbed wires, and graffiti on unpainted cement walls, an unpaved walkway, a broken tire swing instead of a wooden one, and plants that just didn’t seem to be getting the same heavenly sunlight as the ones on the other side. There was a clear distinction between the type of people who live there, and we could see it as we passed by some residents along the way.

As I’m posting this, I’m thinking about how Manu and I only took pictures of the beautiful side, yet the not-so-beautiful side remains imprinted in our minds.

During our trip to Soweto, I remember our tour guide telling us about why so many people in the city have to squat, why the government isn’t doing anything about it, and why they don’t have proper access to water and electricity. If memory serves me right (and anyone please correct me if I misspeak), he said that the homeless usually build their homes on private land, but since these empty lands are still largely owned by generations of White Afrikaans and their families, the government is incapable of interfering and the imbalance of power (through money, property) continues. How are the people of this country expected to present equality—how is the Constitutional Court expected to represent transparency—if they are still living within the limits set upon them by history, with no forward sight of a true rebirth? If the logo of the South African Constitutional Court depicts “Justice Under A Tree”, how will anyone be protected if not everyone is fully shaded by its leaves?

I write all this in continuous reflection of where we’ve been these past few weeks, who we’ve met, and what we’ve learned. I write none of this in criticism of a country that is not my own, as I so desperately and optimistically hope to see that South Africa can continue to turn the tide of change and justice within my lifetime. This place has become an important home of ours (though I admit, we are mostly only exposed to the good—no, great—sides of it), and I personally hold the country in the highest regard for being able to recognize the injustices of its past and reclaim their people’s story moving forward in righteousness.

(As I think Isabella mentioned in her blog post before) I can’t help making comparisons with my own country—the Philippines—and thinking about how my people have ignorantly forgotten our dark history during the Marcos regimen and Martial Law despite our motto being “Never Forget”. Now, our next President is the son of the same dictator, killer, and thief, I know we have an eternity of a way to go before we even reach the level of self-awareness and restorative justice South Africa has with their current republic. In a way, I am envious; and yet more determined to play an active part in bringing my country the real freedom it deserves.

Similar to how an artist looks to a maestro for inspiration, I can only pray that my people and the people of South Africa continue to march forward in their respective fights, for as the neon sign on the Constitutional Court states, “ALUTA CONTINUA: The struggle continues”.